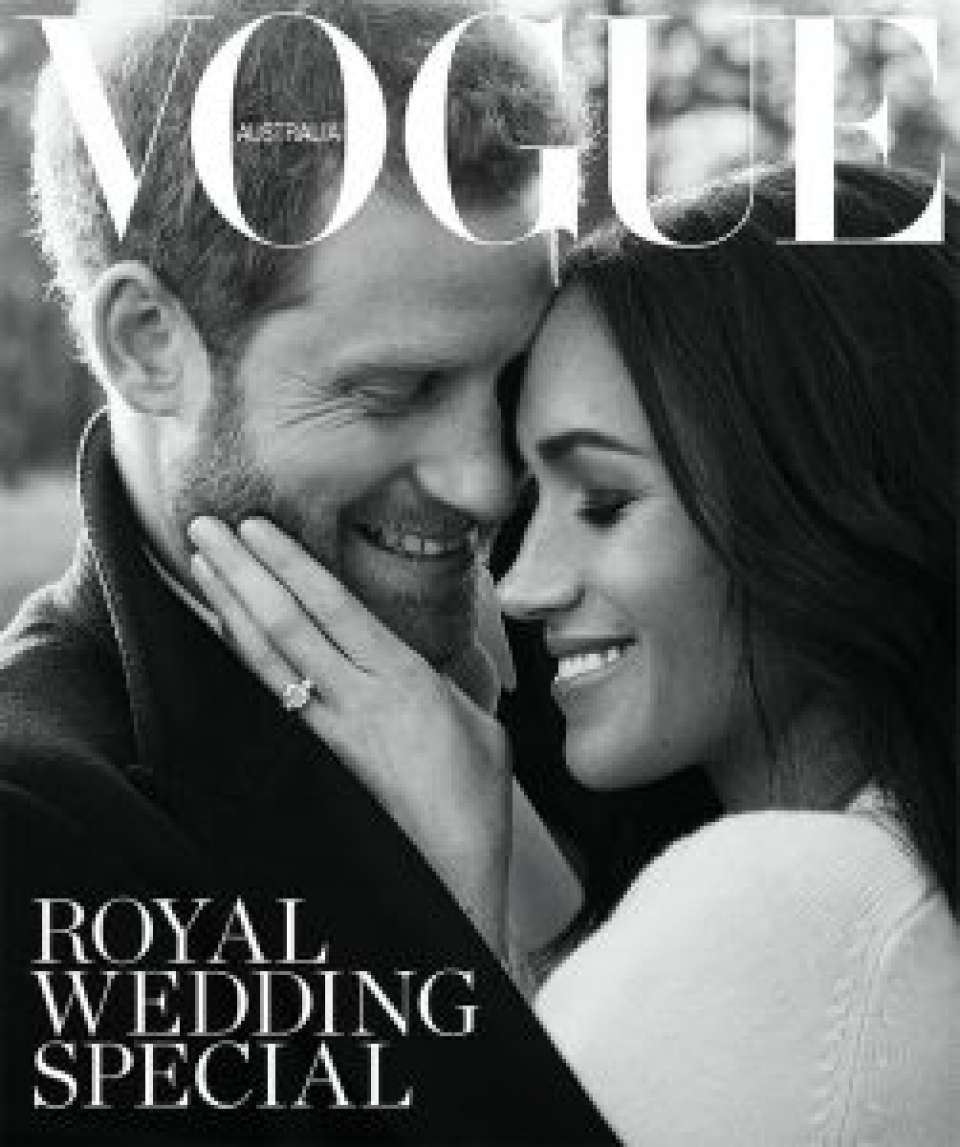

Royal Vogue Weddings

Vogue Weddings

Featuring Prince Harry and Meghan Markle’s wedding and a history of royal nuptials, Vogue Australia Royal Wedding will go to print within 24 hours of the couple’s wedding taking place in Windsor.

The 156-page special issue will celebrate the history of royal weddings – from decade-defining styles to sparkling tiaras and the best of the British royal weddings. It will also showcase the most feted European weddings including Prince Rainier and Grace Kelly of Monaco, Crown Prince Frederik and Mary of Denmark and royal nuptials in Norway, Sweden, Greece and Spain.

The Vogue Australia team will work throughout Saturday evening and Sunday as Prince Harry and Meghan Markle’s nuptials take place to get the final pages to the printer by close of business Sunday. The magazine will be on sale Monday May 28.

Vogue Australia editorial director Edwina McCann said: “Along with producing the special issue, the Vogue Australia team will ensure the best live rolling coverage across Vogue.com.au and on social media as the wedding takes place on Saturday evening

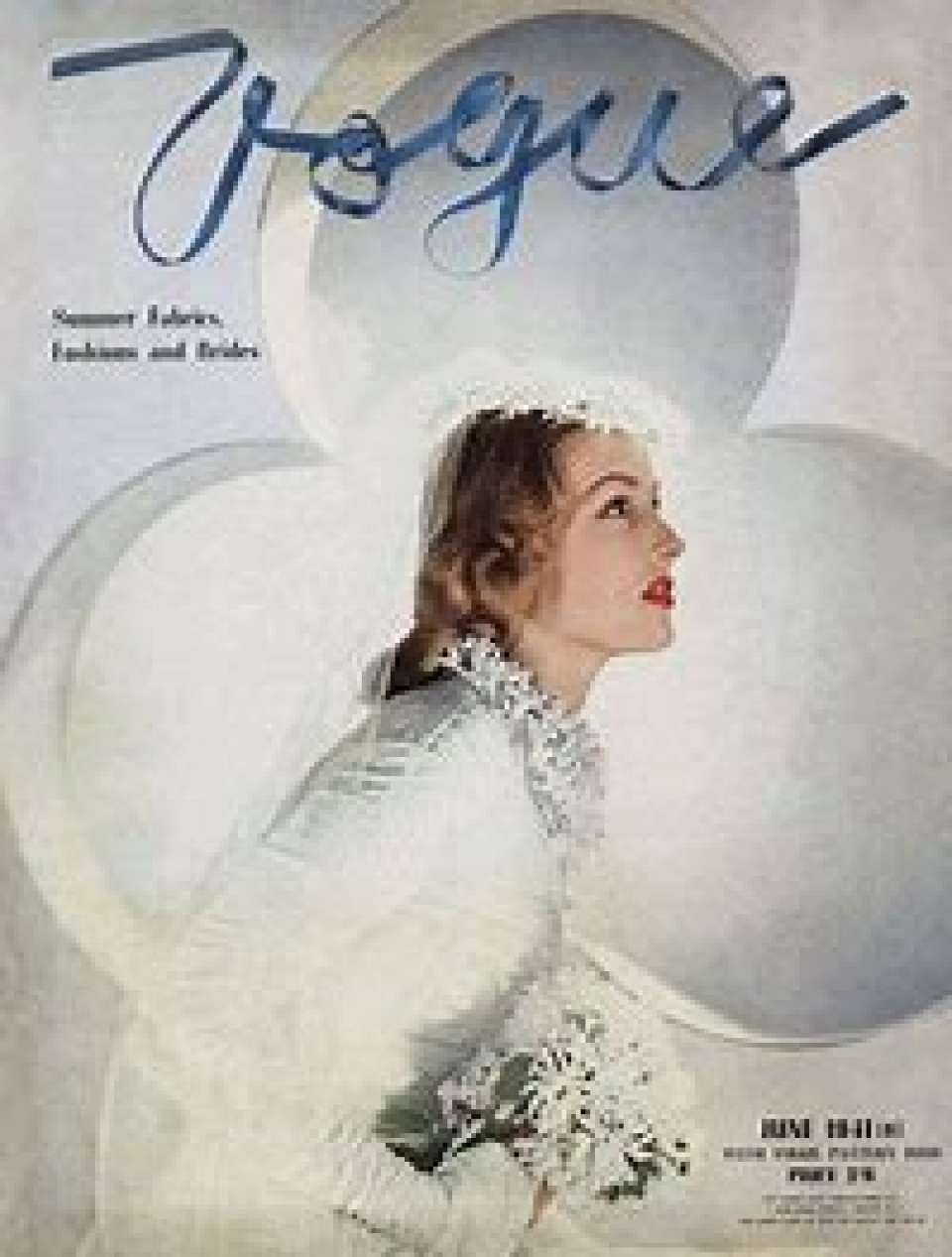

While speculation over Catherine Middleton’s dress has apparently consumed most of the fashion world, Vogue takes a longer view. We look back at a century of royal brides and their style choices, as chronicled in the magazine.

Lady Diana Spencer looked to relatively unknown designers—David and Elizabeth Emanuel, recently graduated from the Royal College of Art—when she wed Prince Charles in 1981. Lady Diana was first introduced to the Emanuels’ work when she wore one of their feminine blouses for a Vogue sitting with Lord Snowdon (the self-same Tony Armstrong-Jones). The Emanuels’ wildly romantic Victorian wedding dress, with its 25-foot-long cathedral train and frothing ruffles fulfilled the public fantasy of a fairy-tale princess. (The nineteen-year-old Lady Diana wore a somewhat aging Cojana suit of sapphire blue for her official engagement photograph and interview with Prince Charles. Miss Catherine Middleton chose a dress of the same color for her photo call with Prince William, but its sleek and body-revealing lines illustrated her own fashion assurance.)

But of course nothing could be further removed from the majesty and romance of these royal brides’ choices than the austere dress and jacket of “Wallis Blue”—a very strong forget-me-not blue that set off her eyes and her sapphire-and diamond-clip—that Wallis Warfield chose when she shocked the world by wedding the Duke of Windsor in 1937. The Duke had of course renounced his throne to marry the woman he loved. Cecil Beaton, exclusively photographing the bridal couple and reporting on the day for Vogue, noted that the dress gave “the bride-to-be the fluted lines of a Chinese statue of an early century.” (In his private diaries, however, he observed how underwhelming the ensemble was for the occasion.)

Wallis wore pieces by Schiaparelli and Mainbocher for the portfolio of engagement photographs taken earlier by Beaton; she was, of course, under no obligation to dress British even for her wedding. Instead she looked to the Chicago-born, Paris-based couturier Main Bocher, whose own rigorous sense of expensive, disciplined elegance was perfectly attuned to her own.

Fearing that no British museum would accept, she later gifted the dress to the Costume Institute of the Metropolitan Museum of Art where it resides to this day.

Vogue announced the engagement of Lady Elizabeth Bowes Lyon to His Royal Highness the Duke of York in March 1923; in her portrait by Beck and Macgregor, her profile is framed by the upstanding fur collar of her coat and by a velvet hat trimmed with ostrich feathers.

In June of that year, Vogue published an elaborate drawing of the wedding ensemble that she chose, with its dress “of silver lamé embroidered with seed pearls suggesting a medieval Italian robe,” veiled in lace lent by the groom’s mother, Queen Mary, (and no tiara—just a chaplet of leaves). The whole look was an apt complement to the soaring perpendicular arches of the Abbey’s inspiring architecture—and to a storied setting that saw its first royal wedding in 1100 when Henry I of England married Matilda of Scotland.

The dress was made, as custom decreed, by a British couturier, in this case, the distinguished and conservative court dressmaker Madame Handley Seymour (who would later make Elizabeth’s 1937 coronation gown). However, its design was closely based on a dress created by the Parisian couturier Jeanne Lanvin, whose romantic designs accorded with the taste of Lady Elizabeth of Glamis.

(Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother’s granddaughter, Princess Anne, also looked to the Middle Ages for inspiration when she wore a dress with hanging sleeves and embroidery of pearl trelliswork, designed for her by Maureen Baker of the Susan Small label, for her first marriage, to Captain Mark Phillips in 1973).

Queen Elizabeth’s daughter Princess Elizabeth (later Queen Elizabeth II), looked to the Renaissance when she wed the dashing young captain Philip Mountbatten in 1947—or at least her couturier Norman Hartnell (later knighted for his efforts in creating iconic images for two generations of royal ladies) cited Botticelli’s c.1482 painting Primavera as the inspiration for the elaborate embroidery motifs of scattered flowers on the rich duchesse satin dress and the tulle veil. The theatrically minded Hartnell, whose clients included royalty, society beauties, actresses, and the romance novelist Barbara Cartland, was famed for his magnificent embroideries, and he employed hundreds of embroiderers in his Mayfair workrooms.

Princess Elizabeth had first been dressed by Hartnell when she and her sister, Princess Margaret Rose, were bridesmaids at the 1935 wedding of her uncle the Duke of Gloucester to Lady Alice Christabel Montagu Douglas Scott (who was dressed by Hartnell in remarkably understated blush-pink satin; her father had recently died, and the planned stately wedding was dramatically scaled down as a result).

In the face of postwar austerity, hundreds of brides-to-be across the country sent Princess Elizabeth their clothing coupons so that she could have the dress of their dreams.

When Elizabeth’s fashionable sister Princess Margaret married Antony Armstrong-Jones (a sometime Vogue photographer) in 1960, the couple encouraged Hartnell to suppress his more exuberant fantasies and instead (and very much against his own instincts) produce a streamlined version of the hourglass ball-gown silhouette that suited her Elizabeth Taylor–like figure: acres of masterfully worked white organza with no embellishment at all. Vogue declared her “a new princess; her dress, unadorned, struck a clear true note.”